Part 1, Seeing the Obvious – the OG alternative to trowels, brushes and data-science.

‘histoire est une suite de mensonges sur lesquels on est d’accord’ (‘History is the lie we can agree on‘) – Napoleon

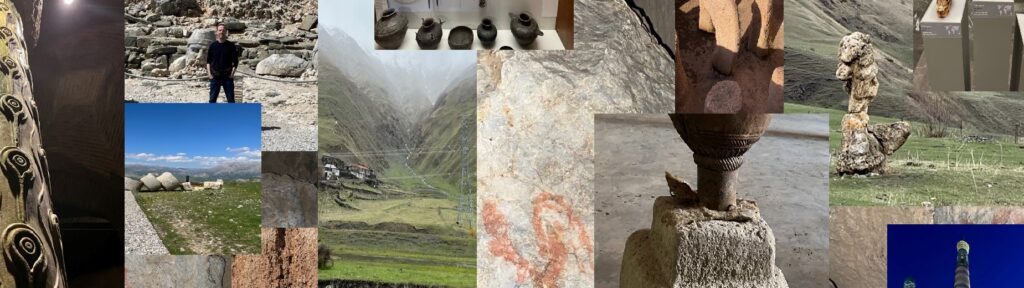

Karahan Tepe PanoramaBelow are several photos I took of the sites and the area surrounding Gobekli Tepi and Karahan Tepi. What follows is a three-part series of postings where I will first share my observations of the sites and the known signatures of the civilizations in this region, and then break down its history based on new evidence. I will model our past based on the data, not the models, and iterate in the future based on community feedback. In other words, I hope to help opensource ancient history.

In this first part I will discuss what we know and can know at this point and attempt to move the conversation in a direction that may help us better understand the people and culture who built this civilization. In part two, I will provide a detailed climactic and geographical backdrop to the story, and show how this region, or any region of our ancient past, simply cannot be understood outside of the context of climate and geography. This may not sound particularly interesting, but there was plenty of climate related action at the time. I will also frame the larger, regional backdrop. Finally, in part three I will zero in on the peoples and cultures of Gobekli Tepe and the larger region, tracing the art, symbology, and architecture back far into our deep, ancient past.

Throughout the series, I will work across the fields of archeology, linguistics, and geology to demonstrate the challenge that is specialization in the science related to the study of ancient history. The new science and new discoveries are happening at a rate that makes it very difficult to curate into a cohesive narrative, but the big picture is un-seeable without considering the high-quality evidence from all of these fields (and discarding the bad quality stuff). The goal of all of this is to use the example of ancient Anatolia to surface many of the shortcomings/failures of our current models. which obfuscate the evidence, mystifying what the new (or newly considered) evidence actually says about our ancient history.

readme.first

It is with my whole heart that I thank the Kurdish, Turkish and Syrian peoples of eastern Turkey for the warm and hospitable welcome extended to me in my visit in the month of April, 2023. You have suffered an unimaginable tragedy and it was an honor and privilege to have spent time in your astoundingly beautiful region. Words cannot express the deep and heartfelt respect and gratitude I have for you all. You represent the very best of the human spirit.

اَلسَلامُ عَلَيْكُم وَرَحْمَةُ اَللهِ وَبَرَكاتُهُ

Second, I want to urge the world, without reservation, to visit eastern Turkey and lavishly spend your money in the region. I have had countless discussions with the local people and with no exception, their wish was that I spread the word amongst my friends, family and community to please come and visit eastern Turkey. This may sound crass, but it is not. Despite the apocalyptical suffering the region has endured, life much go on, and the livelihood of a large number of local people depends on tourism. There was a time when it was clearly not appropriate to visit, but this time has passed. Please, go to eastern Turkey and spend lots of money.

–

In April and early May of 2023, I drove nearly 4000km through central and eastern Turkey, the profoundly beautiful and historically incomparable heartland of ancient Anatolia. I had mixed feelings about visiting at this time for obvious reasons. Thankfully, I have a few close Kurdish and Turkish friends, who strongly encouraged me to visit. So I went.

As could be expected, it was not a typical tourist season. I arrived at the tail end of Ramadan, and the first two days or so there were many Turkish and Kurdish families out and about. That was nice. But after the local people returned to work with the end of the holiday, I was pretty much alone in most of the archaeological sites and museums I visited. I think the entire trip I saw two or three people who appeared non-local.

The cities of Urfa and Antep are, for the most part, running pretty much as they did before the disaster, but there were some places I traveled through that were heartbreaking on the deepest imaginable level. It is truly pathetic the things we complain about on a day-to-day basis. But I also witnessed examples of the human spirit at its finest, many times, and it was life-affirming. And that helped to take the edge off the brief moments of terror that struck every time I felt an aftershock, which, at least when I was there. Happened once or twice a day.

I like to drive when I travel. It allows me the flexibility to get off the beaten path and stop whenever and wherever I want. The local people in this region are amazing, and I spent as much time with them as I could. And what’s more, the food, especially the food of Antep (Gaziantep), is off the charts. It’s every bit as sophisticated, complex, and nuanced as the food of France, Japan, Mexico, Georgia or any other great culinary civilization. You can tell a lot about a people by their food,

Another nice thing about traveling alone, especially with a car, is that it’s disarming to the people you meet. In many areas I visited, I was clearly out of place and I looked it. It is a human instinct to take pity on the lost or stressed out non-local navigating Antep rush-hour traffic, or parked on the side of the road completely lost. It’s a conversation starter, people offer to help and one thing leads to another and the next thing you know you are drinking tea with a shopkeeper or a teacher. Those are nearly always cool experiences.

I had one of those experiences at Karahan Tepe (KT), and in the surrounding areas just north of the Syrian border. Like Gobekli Tepi (GT), Karahan Tepe is a megalithic complex that defies simple explanation. It is very old, possibly antediluvial*, that is, possibly dating well into the last ice age. KH is also widely believed to pre-date GT, but as we shall see in a moment, both are just the tip of the iceberg of what’s to come.

As was often the case, I was the only one at the site. It was 7:30am on a beautiful day. The cool morning had warmed up to about 20 degrees, the sky was blue, intermittently dotted with lazy clouds, and as far as I could see the rolling hills were blanked with wildflowers, bright yellows and reds, mixed among the light, green grass of the early spring.

The road leading to the site is small, paved for most of the way and then gravel for the last 1km or so. A small tourist center building sat next to the gravel parking lot, but it was closed. Ordinarily I would have waited for the place to open but there were no signs indicating it ever would, and I found myself in this situation regularly during the trip, as did many local tourists. Places opened intermittently, or not at all, but many are open-air sites, with no distinction between the site and the surrounding landscape. I was at dozens of places like this where local families would enter the site, even if officially closed, and walk around taking pictures of their kids in front of the ancient rocks, while enjoying the spring weather. I learned to just follow their lead.

When you see something like that close up, it boggles your mind. I just stood staring at the site and the surrounding hills, it is a lot to take in. I think it is human nature to unconsciously impute meaning and significance on such a place (the Internet is full of pretty creative stabs at doing so), but I tried to avoid it. Which took a lot of effort, because my frame of reference is clearly inadequate, but I wanted it to make sense.

I quickly came to understand that there was a much bigger picture spread all around me that was fairly easy to understand. So that’s where I focused my attention.

A young, plain clothes Kurdish guard eventually showed up with his son, who was about 6 years old. No one speaks English in that part of Turkey. Kurdish or Arabic are the first languages, with Turkish as a second, but mobile phone reception is decent and everyone has smartphones, so translation apps can be your best friend.

After chatting with the guard for a while, he basically gave me free reign to go where I liked so long as I was careful. After wandering around the KH site for maybe an hour while he played with his kid, I approached and asked him about the stelas (pillars) I see in the distance, several are visible. He waved his hand across the landscape and said, in essence, they are everywhere. I asked what percentage he feels have been excavated and he replied, again I paraphrase, “way less than 1%”.

Although GT and KT are similar in many ways, there are clear differences in style, layout and scale. GT has far more elaborate figures carved throughout the complex. By comparison, KT is less elaborately detailed, and at first glance, appears to be smaller, but the complex remains largely unearthed and the ultimate scale will reveal itself over time. Despite the style differences, the similarities in construction and organization suggest some degree of cultural relationship. Most of the known settlements around the world dating to this time are something akin to a federation of closely related peoples with varying differences in the culture of the individual units.

Of course, this is a purely observational hypothesis. It is very possible the sites are separated from one another in time by centuries or even millennium, and that the str. It is also very possible that they are separated by centuries or millennium and almost certainly by different peoples at different times. For whatever reason (there are reasons), this is something that is not widely discussed, but very few ancient settlements like this were occupied by just one culture during one span of time. It would be quite surprising if this was not the case in this region (contrary to the prevailing perspective),

The sites are about 15km or so apart and estimated to date to between 10-11,500 years ago (estimates vary, and they are quite possibly wrong – the founding architect dated in highly sub-standard ways, which has gone largely unchallenged). And there are others in the region, the largest of which is Boncuklu Tarla (BT) in the Mardin region, roughly 400km east of GT. It is believed that BT may predate GT but there are virtually no human or animal remains that have been found in any of the known sites, which makes exact dating difficult (which is largely restricted to organic matter – see date comment above).

What is clear is that the scale of these settlements is far greater than what we can see based on current excavations. The surrounding area is literally dotted with stelas poking up from the ground. If I were to estimate the total geographical scale based on what I observed (more on that in a moment), I would guess this ‘settlement’/’settlements’ stretch over an area greater than 500km in diameter. Of course, no one can say with certainty the nature of relationship between these various sites or the degree of contemporaneousness, but assuming they were all build by peoples with some degree of shared culture, these are not settlements, this was a civilization or multiple civilizations on an astounding scale vs. our current model of human settlement at the start of the Holocene (the end of the last ice age).

How can I be sure that what the guard told me, and what I saw with my own two eyes, were stelas and not simply odd shape rocks popping up across the landscape?

This is not the kind of thing you can answer with a Google search, and even if you could, it is always prudent to take search results with a grain of salt (to state the obvious, ‘accuracy’ is not a metric used to algorithmically order and prioritize search results). To know for sure, I had to get up close and personal with a few.

On the drive back from KT to Urfa, I stopped to talk to a shepherd and a farmer. They were surprised to see me at first, and a little taken aback, but we warmed up to one other. After fumbling between Kurdish and Arabic on my translator app (the shepherd was Syrian and spoke Arabic), I asked them what they could tell me about the stelas and the region in general. They confirmed what the guard had told me and after chatting a while, the farmer brought us both behind his house to a stable built from large stones collected in the area. Several were carved, unmistakably in the same style as the stones at GT and KT. He said there were a lot more in the stone walls surrounding the farms of the area. I asked if I could hike up into the hills and across his field? His reply, in essence, was ‘go to town!’ I hiked in the area for nearly two hours and stopped at several stelas. I pushed on them, at first gently to see if they would budge (the shape is such that if they simply rested on the surface, I could likely push them over). They didn’t. So I pushed progressively harder. Nope. I then put my back* into the job, leaning against the stone using my legs for more pressure. Zilich. They don’t budge. They run deep.

The exposed surfaces have eroded to the point that if there were any carved reliefs, they would not still be visible. Nonetheless, I dug around the perimeters with my hands and then with a flat rock. After about 10 minutes of that it was absolutely clear these were carved stone stelas and the part protruding above the earth was just a small fraction of the total height of the stone.

It might be also helpful to point out that the most ancient examples of ‘narrative art’ (whatever that means) was found in the home of a farmer in this area. The art piece is a carved stone relief of a man with what look like leopards attacking from sides while the man clutches… well, see it for yourself). For years this art piece was an item of curiosity, one of many local stones that was used to build the wall of his house. One day he figured it might be good to have an expert take a look at it, and it turned out to be ancient, dating to roughly the same time as GT/KT.

Returning to my back of the envelope estimate of the geographical scale of these sites…

A few days after visiting KT and GT I made a futile attempt to visit the Karkemish (Charchemish) archeological site, which literally straddles the Turkish/Syrian border and lies about 150km southwest from KH. It turned out the site was closed and inaccessible (or insanely stupid to try and access). I got as far as the gate, beyond which was the final stretch of gravel road that led to the site. I took a few pictures of what was visible (nothing, really) but then got chased away by angry dogs. No one else was around and I probably didn’t look like I belonged on their turf. Nonetheless, it’s a hugely important area, historically, the literal bridge between Anatolia, the Levant and Mesopotamia (which is key to understanding the history of the region, and something I will explore in part 2). For at least 3000 years prior to the founding of what is widely considered (albeit wrongly considered) the first Sumarian empire of Urick, the region was populated by multiple peoples, cultures and languages, and it served as the nexus of trade and exchange between the Lavant, Mesopotamia and Anatolia, among others.

The dogs freaked me out a bit, but I took advantage of my time there and saw a number of other local archeological and historical sites, and stopped for menengic coffee, one of the treasures of life in that region, and a drink impossible to find outside of Kurdistan in anything resembling the real thing.

On the drive back from Karkemish to Urfa (Sanliruifa), the largest city in the region and another profoundly beautiful and historically rich place in the region, I was constantly scanning the hills on the remote chance that there might be similar stelas in that area. Unexpectedly, there are. About 75km from Urfa, maybe 100m from the side of the road, I spotted some similarly shaped stones and so I pulled over and hiked up to them. On the way I had to step over a knee-high barrier that marked the perimeter of the farmers field, which are common in that area. They are all made from piles of stones removed from the farming plots and in many ancient places I’ve been in the world.

Unsurprisingly, the ‘fence’ was full of large chunks of unmistakably carved stone. And when I arrived at the stela-shaped stone I saw from my car, it was clearly the real-deal.

I spend a lot of time carefully inspecting structures like this, sometimes noting stones, one by one, that lay at the foundation of historically important monuments and structures. Quite often, small bits of our ancient past appear in the lowliest places, and traces of our ancient history are there to see if you look for them, especially in the walls of very old buildings. Nearly all human history is the product of a series of conquests, whether militarily, genetically, or culturally. In rebuilding over the rubble remains of a sacked village, why cut all new stone when you can use the perfectly good ones from the rubble. A very large number of ancient structures are built on the foundation(s) of earlier, and more ancient structures.

Here’s an unrelated example from the high Caucus mountains of Georgia near the Russian border.

The reuse of stones and the building of new structures on the foundation of much earlier structures is ubiquitous through the ancient world. The damage from the earthquake was still widely visible when I was in this region and on many occasions, this exposed clear examples of multiple generations of ancient stones mixed amongst the rubble of a collapsed wall, or foundational stones very different and clearly far older than those used to construct the wall above. In a few instances, I could roughly age the earlier stones by the carving marks/techniques. Ancient archeological sites are nearly always excavated in layers.

Prior to modern dating techniques, the lowest of these were almost always misdated to a much more recent time. Our paradigm of ancient history has a start-date inherent to the model and until new tech forced their hand, very, very few archeologists challenged those start-dates, often vehemently dismissing evidence of much earlier peoples. When the late archeologist Marija Gimbutas first proposed the existence of a vast early to mid-Holocene European peoples with deep cultural roots and large, highly organized settlements dating between roughly 12-3000 years before the height of ancient Sumaria, she was roundly dismissed. Although I disagree with many of her ideas regarding the culture of those civilizations, it was largely her work that surfaced the diverse, wide-ranging, and artistically masterful peoples of Old Europe.

As I will explore in part 2, there are clear ancient, historical continuities running through these ‘Old European’ peoples and Anatolia that date back at least 20,000 years before Gobekli Tepe was constructed, whole civilizations and threads of continuity that simply cannot be modeled using the current paradigm.

So back to my guess of the scale. Assuming the most conservative scenario possible, that Bocuklu Tarla forms the eastern most border of these settlements and the stela west of Urfa lay at the western most border, the diameter would be roughly 400km. Given the unlikelihood of those sites actually representing the geographical fringes (it is more probably the ones I didn’t see represent a more accurate geographic perimeter), it is very possible this civilization/these civilizations stretch across an area in excess of 500k or possibly 1000km or more.

It is important to note that I am using the term ‘civilization’ very loosely and in a way closer to the use of that term in describing the Natufian, or the Chinese Yellow River settlements or the various settlements referred to in the kindergarden vocabulary of contemporary paradigmistas as the Iron Gate Mesolithic peoples on stretches of the Danube in the Balkans, etc. These cultures are often not a contiguous and homogeneous group of peoples, but instead a patchwork of culturally or genetically related but varying groups. What is unique about these sites in ancient Anatolia is they are not connected, loosely or tightly, by a shared river or body of fresh water (i.e, Mesopotamia on the Euphrates). In fact, there isn’t really any significant body of fresh water in the immediate areas surrounding any of the sites unearthed to-date, although it is very possible there was at the time**. The other unique thing, of course, is the awe-inspiring and thoroughly vexing arrangements and carvings of the complexes.

In part two of this series, I hope to show that as awe-inspiring and vexing as these places appear, there is precedent for much of what we see in these sites, both within and outside of Anatolia, and there are elements of these cultures that can sensibly be placed in a continuity of our ancient past. But Anatolia has always been its own thing in many ways, and I am convinced that as we pivot the spotlight of inquiry away from the stage of our current paradigm we will come to understand far better just how special Anatolia is.

–

Before wrapping up, I wanted to share some thoughts and speculations about these sites, and also some thoughts on speculations about these sites.

First, as discussed in my intro post, it is futile and non-descriptive to refer to the people who constructed this (or these) civilizations as ‘hunter gatherers.’ As per my introductory posting, language matters, and a new vocabulary is required to describe the complexity and nuance of the peoples and cultures of our ancient past, and this is a very good example how the baggage of an outdated term shackles both an honest and thorough inquiry and understanding our ancient past. In this case, it leads to silly and distractive discussions about which came first, agriculture or settlement?

That debate is a product of the current language and model. If we assume agriculture popped up simultaneously in several parts of the world around 5-10k years ago, we are forced to reconcile agriculture and settlement within a model whose timeframe struggles to explain both. Remove, for now, the constant that is the presumed widow of time in when agriculture first appeared, and this discussion becomes moot as factor in the history of humanity in the Holocene.

Second, as mentioned earlier, it is difficult to avoid imputing meaning on places/peoples like this, but I believe it’s largely futile for the time being. As more sites are excavated, more evidence will come in, and as it does a picture will emerge (along with additional genetic data) that will help us start to understand the peoples of this civilizations in far less mystical or speculative way.

And although it is probably fun or headline-grabbing (blog paying) to impute astrological and apocalyptical significance on the symbology and layout of these complexes, or to declare Gobekli Tepi ‘The First…” of anything, is to chase a red herring, just as it has been in Mesopotamia.

As anyone who has searched the term “Gobekli Tepi” knows, there is a great deal of articles, papers and Internet blog fodder describing Gobekli Tepi as “The World’s First Temple”, or “The World’s First Civilization,” or to ascribe elaborate apocalyptic or astrological meaning to the symbology. I know my mind has gone there,, but we have unearthed so little of the area, and still know so little about our deep ancient past, that there in the larger timeline of human history, it is almost certainly not the ‘first’ anything. It is also highly problematic to unduly establish foundational inferences without a lot of data. In archeology, it is considered somewhat uncool to challenge the inferences of the ‘founding’ archeological team. But what follows can’t help but build on (or prove wrong) those initial inferences. It becomes a de facto intellectual starting point and to some degree, it always colors interpretations of later research. Speculating is fair game and helpful. ‘Establishing’, especially in research papers that become headlines that lack details can quickly become irretractable. “They say” X, Y, or Z becomes “it was” X, Y, or Z, often and easily.

And what’s more, it is very difficult to find any real evidence to support the notion that any of our ancient ancestors gave even a miniscule thought to humans in the distant future. I am not sure when the notion of prophetic warnings became a thing, it may have been the Christian era, I don’t know, but even the Hebrew Bible lacks apocalyptic warnings about the future of humanity. Are there warnings to the future of humans of that era? No doubt. Ancient people left reams of texts about the consequences that would befall a people if they failed to heed the decorum or belief-structures of their times. But as far as I can tell (or remember reading), pre-Christian prophetic judgment was mostly aimed at the here and now (there and then), or the future survival of their specific future generations. Please correct me if I am wrong or missing something. It is probably sensible to infer that our ancient ancestors had bigger things to worry about than the future of the iPhone, ancient alien generation or distant, unrelated generations of any era other than that which was comprehendible. There are more parsimonious, evidence-based, and sensible ways to understand the symbolism, some of which I will suggest in part two.

That said, while I was there I heard a few speculations that seemed at least remotely plausible.

When visiting the Gobekli Tepi site, there was a French woman tourist with a Kurdish guide. Like many guides in Turkey, he was almost encyclopedic in his knowledge of the history of the area, and highly thoughtful. I stopped by to say hello just as he was describing the most famous and well-known chamber of the complex, the large circular space surrounded by 12 (a couple have fallen over, but you can see their bases) intricately carved stelas. He said two things that were interesting. The first was that there are 12 total, aligned roughly to the sun at the time (and still to this day, to a large extend), essentially forming a giant sun dial. It was about noon at the time and sure enough, it was a pretty accurate clock.

Many ancient sites around the world function as timekeepers for seasons and even hours of the day. An agrarian culture that is wholly dependent on the seasons and knowing the time of year/day (when to plant, how much longer must we suffer through this winter, etc.) is often a communal necessity. This seemed sensible, but it raises an interesting question: why the number 12? The base-12 calendar was thought to be invented in ancient Sumar, and if so, was this coincidental?

I cannot say with certainty that the stelas are arranged as a sundial, nor can I say much about the antecedents or reasons for base-12 time. But I can say with certainty that we know now that a great number of things thought to have been invented in Mesopotamia were simply not invented there. Examples of written scripts in Europe pre-date the first Samarian hieroglyphs by at least 2000 years, and examples of writing independently “invented” appear all over the world. It is the same for agriculture, medicine, and many, many other mis-labeled ‘inventions’ of our past.

However, to speculate further but somewhat sensibly, one fairly unique thing about Anatolia is that there have been long periods of Anatolian history with comparatively low levels of genetic change (ve Europe and Mesopotamia, for example). And Anatolian history is clearly very ancient. For these reasons and resaons I will explain in part two, it is not out of the question that the origins of base-12 starts or runs through Anatolia in some way.

The other thing he said was to note the similarities between the bird reliefs and the giant, now extinct birds of Madagascar. This seemed to me more of a stretch, and if he would referenced large, extinct birds form any other place on earth, I would have abandoned the thought immediately. But Madagascar is one of those unique outliers of our ancient past and the bird symbol, often represented in virtually the same way, morphologically, is broadly and ubiquitously used around the world to at least the first millennium BC (and perhaps in related but far more ancient forms dating back another 30,000 years).

One of many unique things about Madagascar is that before European sailors ‘discovered’ the place in the 16th century AD, it had long since been settled by the great sea faring peoples of Oceana, most likely from the area near modern Java. The island lies roughly 300 miles off the coast of Africa but there is no evidence that it was ever settled by indigenous, continental Africans. What’s more, there is ample evidence that the giant birds co-existed for a long period of time with these ancient Oceanic settlers. Of course, none of this explains why they would carve these figures at Gobekli Tepi, but the chance of some connection existing is greater than zero. The bird motif, represented in similar ways, was common in sites populated by the earliest known peoples in what is now Corfu, Greece around 6500BC, the peoples of Malta at roughly 3000BC, and in pre-Minoan Crete, all sea faring peoples. It was also found on carvings in Sumaria and elsewhere in Mesopotamia dating to at least 3000BC. This is no doubt a stretch, but it’s not impossible. Our ancient history exhibits a great number of continuities that defy probabilities. Also, some of the most frequently dismissed, or completely ignored, clues in archeology are those found in symbology (see Flood post).

I’ll stop here for now. Thank you for reading, I hope you enjoyed. Please send me any comments or suggestions, and as always, I remain open to being wrong about any of this. If I missed on some or all things, let’s get it on the table and figure it out.

.***

References:

I intentionally minimized detailed references in this post, I wanted it to be less academic and more personal. Moving forward, I will include complete references at the bottom of each post or as hyperlinks in the text.

*This word was very intentionally chosen. More to come on that.

**There is a great deal of high-quality, fine-grained, large- and regional-scale research available exploring the climactic, geological and oceanographic history of Younger Dryas (YD) transition into the Holocene in North America. By comparison, there is very little of this for continental (i.e., non-Atlantic/Med) Europe, Anatolia, Central Asia, Mesopotamia and the Far East (the exceptions being the Levant/Maghreb). The presumption appears to be a comparatively (vs North Amer) long-duration melting of the ice sheets with runoff largely routed into the north Atlantic at the start of the YD, and only much later (~8-7k ya) does the Black Sea to Aegean/Med via Turkish straits meltwater path appear, and in a far less dramatic and longer-term scale than nearly all of the recent N. Amer meltwater scenarios proposed. Suggestions on quality research specific to small-scale (sub-country level) climate during the YD-Holocene transition in Anatolia, the Balkans and E./S. Europe would be much appreciated, particularly research related to glacial meltwater paths, timeframes, scale and geological impact would be very helpful,

**Les it be seen as irresponsible or just uncool to ‘put my back into’ a 10,000+ year stone in someone else’s country, it might be appropriate to note that it was one of those “you had to be there” situations, and pretty hard to judge from a distance, IMHO. I was careful in sizing it up, but no doubt I pushed hard, as have many before me. The farmer I met shared that he and other local farmers have tried for generations with everything short of dynamite to get remove the big, unmovable stones from the prime farming plots. One even tried using rope and a tractor to pull it out. For me, it’s a non-issue, it was actually a highly enjoyable experience. But I understand that others draw the line separating what is inappropriate/destructive from harmless/constructive than I do.

Speaking of which, it may be worth taking a moment to consider how that line has been ‘officially’ drawn by the institutional structures of the Paradigmista State for the past century plus. I did, and found myself compelled to write letters to the Smithsonian and other large holders/displayers of warehouses full of Anatolia’s national historical and archeological treasures wholesale plundered from the late Ottoman and current Turkish states by the US, France, Germany, Austria, The Netherlands, Denmark, and England. No matter how you draw the line, this crosses it, IMHO.

In his excellent, meticulously researched, and highly disturbing book, Tears of Anatolia, Our Historical Artifacts That Were Taken Abroad, author Yasar Yilmaz painstakingly inventories accounts the details (names, dates, places, shipping records, etc.) of much of the stolen loot. Although translated into English, it is unavailable on Amazon and I could not find safe link, but here is a pic of the cover.

The research and development of our current euro-colonial paradigm of ancient human history came at a very high cost to Turkey and many other places.